“Well, well,” said a familiar voice. It was, of course, that copper-haired man, the one who had so enthralled me. “What are we going to do with this, huh?”

Of course I was not at my best.

In fact, I was a disgusting mess.

There is such a thing as unwarranted optimism, and I had not navigated the distance to the privy-stool with any particular grace. With predictable results.

“You could call the jarl and have him put me in The Chill,” I suggested, wearily.

It couldn’t possibly be any colder than I was right now. I was lying in my own foul wet, and I couldn’t feel my feet, or my hands, or even my buttocks.

“I am the jarl,” he said.

Ah.

I rolled over, painfully, and tried to put a bright face on it. “Well– help me up. And then perhaps a bath?” I asked, hopefully.

“I’ll get Seloth,” he promised, his beard glinting as he grinned at me. And, more seriously: “I will speak to Thaena. I think maybe she has been feeding you too much rich food too soon.”

“No!” I said immediately. “I just ate too much of it.” And: “I think I can do it if you help me.”

He came over to lift me, and it was almost immediately not-fine; but it was a condition that within a short time had resolved itself.

Once I was empty, at least. What a waste of a good meal.

No help for it; I curled up around myself and brooded.

Back to broth tomorrow; or, gods help me, skyrr.

Malur Seloth was–also predictably– exceedingly unhappy with me, but it did not seem that I had taken any damage to my hands and feet. I was given another severe warning about chillblains and frostbite. And reminded, once again: if it was that urgent, use the bucket. How revolting.

—

—

“When are they coming back?” I asked again, trying not to sound plaintive.

“There’s heavy snow up in the mountains just now,” Malur Seloth reported.

He is friendly enough for a Dunmer, I suppose, though not particularly enthused at taking care of me.

“When it subsides, it should hard freeze and pack all the snow down. Travel should become much easier,” he explained. Dangerous, yes, particularly if the wind shifted– but safer than trying to trudge through whirlwind blizzard or drifting heaps of snow.

Erdi and Ahtar were off on some needful errand for the jarl, and had probably gotten stuck out at Heljarchen after the last blizzard. I had not seen either one of them since I had come back to myself, but both of them had been reported to have come and gone.

Alfgar the Dovahkiin– per Thaena– had gone on to establish a new settlement at a place called Windstad, not too far away from the borderland between the Pale and Hjaalmarch where we had battled the great dragon. He was working there now. Thaena had some small investment in the place. So did Erdi, courtesy of the Jarl of the Pale, in return for some task she’d done for him. Thaena said that the Dovahkiin and his builders would come to Winterhold next. She and Korir had hopes for this place.

Ma’dran’s Khajiit had moonpathed away, and no one knew where they had gone. Thaena said that Jarl Skald was still rather displeased with the caravan leader and that there was a standing order to have Ma’dran hauled into court, to answer questions about his salvage operation. Ri’saad had already come up to Dawnstar to disclaim all accountability, and to promise his assistance in the matter. Skald was not holding his breath.

Marcus– after some rather grievous disturbance of the peace in Dawnstar and a stint in Jarl Skald’s jail– Marcus’ whereabouts were just as unknown. Erdi had told Thaena that she thought Marcus had intended to return to Solitude, but as that was enemy territory these days, communications would be difficult even if the weather cooperated.

—

Interestingly, there were no further rites at the Talos statue.

The little shrine to Julianos in the corner, however, saw regular use. Eventually I asked.

Thaena interrupted her drumming-practice to answer me. But the explanation she gave me made no sense: Julianos– formerly Jhunal– was the townsmen’s deity, and as such had pre-eminence. Well, that part made sense, given the proximity of both the Sea of Ghosts and the College.

Talos was venerated at the indoor shrine on his days of worship, which would include–

“Why?!” I demanded. “Why would you Stormcloaks be celebrating Emperor’s Day?”

Laughter, even from Yllga.

Ah. I had forgotten. We ourselves have another name for that particular holiday: Day of Ultimatum.

The date upon which the Thalmor ambassador delivered to the senior representative of the Mede dynasty a thoughtfully-curated, surpassingly expensive and exceedingly labor-intensive present.

“Well, we may hate the Empire, but–” Korir shrugged. He didn’t need to articulate the rest of that sentence but he did: “Everyone hates you damned elves more.”

He said things like that quite a bit. There was really no need for him to fill in the blanks.

I stretched again to ease my back, being careful to avoid triggering the vertigo.

The long-suffering Malur Seloth happened to meet my gaze. I started to say something, and then stopped. I wondered how he put up with all of this. It took me an embarrassingly long time to discern the obvious.

I wondered, uneasily, just what these people had taken note of when Ahtar had been present, with myself in no condition to guard my thoughts. Assuming I had done or said anything at all.

But none of them said anything to me one way or the other, and I tried not to ask after him too much.

—

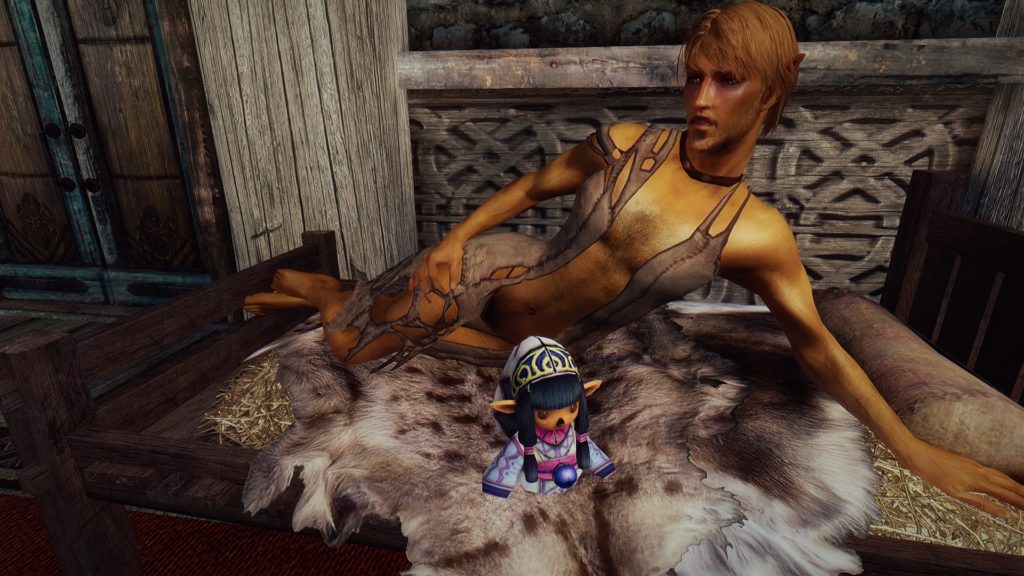

“Why can’t you walk right?” asked Yllga.

I had been humoring her by playing with her dolly, walking it along the edge of the bed and making it speak in the nasally, oh-so-affected voice of one of those Alinor-creche Justiciars.

This was my thanks.

“None of your business,” I said, crossly, as if it didn’t matter.

In fact I was exceedingly anxious about it. My magicka had not come back, at all– and the lack of being able to feel the nodes and leys had left me as disoriented as a cat without whiskers. And my muscles were still surpassingly weak. I could walk, sort of, with the assistance of a few sturdy chairs. Or, when available, a large Nord man.

Otherwise I was limited to the immediate vicinity of the bed.

“Is it because you’re defective?”

Thaena was approaching, face tight.

“Nooo,” I said, slowly. “I just got hurt. And it made me take sick.”

Really, Thaena ought to have no concern that I would take offense. It was a natural question for a child to ask–

“Oh,” she said. And: “Papa says you people drown your defective kynds. Or break their necks. You know. Like when there are too many kittens.”

I sat dead still, heart hitting a triphammer beat. Thaena hovered in the doorway of the next room, aghast.

But this little one– her question was wholly innocent.

“My sister Avrilewyn was… she had a problem from birth,” I said, frowning at the doll and setting it down, carefully. “I think I know what book your papa got that out of, and it is a very ugly lie,” I told her.

Yllga persisted: “Is she dead?”

“She’s gone on,” I acknowledged, soberly. “She couldn’t have lived–but we took good care of her until the day came.”

The blandishments of my elder sisters Cireen and Elenwen notwithstanding. Thankfully, the trustees of my father’s estate had remained unconvinced. Or perhaps they had chosen a more pragmatic approach: there would be no need to upset my mother so, when the expected outcome was known by all to be inevitable.

So.

Like all lies, its seed a truth.

Yllga looked at me, thoughtfully. She asked another question.

But I had already turned away onto my side, facing away from her, eyes closed.

“I think Mathilde should go with you for now,” said Thaena firmly, finally taking charge of her wayward offspring. “Cyrelian needs to sleep.”

A few days later, Thaena took the time to sit with me: “Are you going to be all right?”

“They will not want me back,” I whispered. “I am of no more use to them.”

“It’s only been a little while,” she said to me. “It may get better. Don’t borrow trouble.”

Thaena paused: “Do you know why she was asking?”

“I… think that I’ve put that together now. I overheard some of the things that the herbalist was saying the last time that he was here,” I said. “I’m sorry.”

“Don’t be,” she said. “We do the best we can for her, given the circumstances. And she is doing better, just now, thanks to the Advisor.”

The herbalist didn’t speak much. He conducted his examinations in near-silence, tapping on me here, and listening there; and squinting at the whites of my eyes and the inside of my mouth. I attempted to decline further examination, but the jarl growled at me; and thus I submitted, on the condition that someone remain in the room with me. I could not say why, but I did not trust this human. He felt off-kilter, somehow.

But it would have been ridiculous to say so of this old man, with his tousled and burr-stuck hair. And these people trusted him with their child, after all. So I pretended it was just another one of my annoying, labor-generating idiosyncrasies. Apparently I have a few.

Malur Seloth stood nearby, exasperated, his eyes turned towards Aetherius and arms folded in a posture of resignation, whilst I was poked, prodded, and pinched; and a variety of undignified answers were demanded of me.

Then I was permitted to get the rags of my shirt on and climb back under the blankets, whilst the Breton filled out a log-book, whistling some annoying little tune.

I should note that the appalling condition of my garb had nothing to do with my keepers– they were quite good to me, after all, and rather lavish with their foodstocks; it was just– Winterhold is isolated and cloth is dear and I was still making a mess of myself, from time to time. Thaena did offer, but I felt there would no sense in ruining some expensive new outfit. My lack of control was intensely frustrating.

The herbalist stopped to take a quick glance at Yllga, and ensured that Thaena’s stock of medicaments was still well-stocked. He left.

Malur Seloth had something cutting to say about the waste of his time due to my ridiculous state of nerves, but I was not alert enough to manage a rejoinder.

When the weather improved still further, the black robes of the Thalmor official were sighted once more on the College bridge, and a townswoman ran ahead to warn the jarl.

Advisor Ancano expressed mild surprise at my level of progress, and counseled patience. He spent a great deal more time with Yllga, sitting and talking with her for nearly an hour, playing together with her toys.

After that he took copious notes in his logbook.

Once he set down pen and sanded the page, he went out onto the lookout.

To meditate, he said.

When he came back in he was just as calmly serene as when he had left, but the wind had reddened his face and neck.

He sat by the fire. To warm up, he said. He was silent for a long while.

At this time Thaena explained to me that she and the jarl wished to speak with the Advisor apart.

I told myself that it had to do with Yllga, but I knew better: it had to do with me.

I had their hospitality for the winter, yes– but I was fully cognizant of the calendar by now, and its rapidly-passing days.

The Advisor came back into my alcove, and stood looming near.

“There is no news from Alinor,” he said, in that arch voice of his. “In case you were wondering.”

“Ah,” I said, in such a way as to discourage further response. I did not want to have a conversation.

For all that he had represented my salvation and had been my pole-star for weeks, I did not care for the mer on first acquaintance. For the most part, he does not pretend to be even the least bit personable, which is an odd characteristic for a senior officer assigned to the diplomatic corps.

He is also one of those annoying persons who takes an inordinate amount of care over his personal appearance, almost to the detriment of everything else. Advisor Ancano had gone so far as to polish the clasps on his blacks for this little errand of ministering to the sick. His silvergilt hair was immaculately tended; his fingernails freshly manicured. I have seen mer less well-put-together who were headed to testify in front of the Convention. I was not at all surprised to later learn that he was not at close purposes with Elenwen.

I do miss her acerbic little observations.

Even then, I knew why Ancano maintained such habits: he is not one of us. Not really. Despite his looks– which are probably what caused him to be presented to the doctrinal school in the first place–he has nothing more in common with the glories of old Aldmeris than one of our ditch-diggers.

Maybe less.

Those folk at least attempt to maintain some vestige of a lineage. The good Advisor, I later learned, never knew anything more of his kinship than his mother’s name and the fact that she was a recusant and almost certainly a whore.

Little Yllga’s barn-birthed cat has more pedigree than he does.

I have no idea why he continued to stand over me and regard me with disfavor.

I lay quite still, breathing slowly, and prayed he would go away.

No such luck; he settled himself in for the duration, sitting down on the rug to stare at me. Giving me a headache.

“I did not expect there to be any news,” Advisor Ancano said at length. “Your name is not to be found on any of the missing-in-action or unsanctioned-leave lists.”

Had there been that much disruption in Haafingar, then? That was curious.

He was silent. Counting my respirations or some such. Aggravating.

I broke first: “What is my currently posted assignment?”

Since, of course, I was here and not wherever-that-was, I supposed I could add dereliction-of-duty to what would be an already stunning collection of demerits.

“That is something else that is curious,” said the Advisor, disapprovingly. As if all this were my fault. “I receive the monthly updates on our posting information as part of my duties for the First Emissary– and I have never seen your name on any one of them.”

He coughed. “Nor did I see you on any of those commencement lists which the First Emissary insists on sending along.”

I said nothing.

“When I return we shall speak of this further,” he warned; that was the Justiciar-in-charge voice, as cutting as Sun’s Dawn ice. An ultimatum.

I could not quite control my demeanor; thankfully my face was mostly-buried in the pillow. I swallowed past the fear and made great efforts to calm my breathing; the ugly hammering of my pulse.

I did the only thing that I could do; I feigned sleep.

Advisor Ancano vented a noise of disgust, but at least he went away.

Advisor Ancano’s update was not merely dismaying; it was terrifying. According to the official bulletins, I was not missing.

No one with any vestige of proper authority had no idea where I was. For all anyone knew, I’d been dead for months– or had never even existed at all.

It is one thing to be trapped in Alinor’s vast and uncaring bureaucracy– needless to say, it does not keep one’s best interest at heart.

But it is quite another to realize that one is wholly lost.

Recent Comments